by Dave Kessler

11 November 2023

Tiger Intears believes he’s the most inspired writer in America. Eight years after establishing a creative practice for the first time as a college student in New York, he’s just put out a website and a debut essay: Stained Glass Sincerity, in which he talks of Joseph Beuys and obscure Scottish football matches, along with discussions of faith, especially its venn diagram intersection with artistry. Next year, he’ll be releasing a collection of early essays titled An Angel Moves Too Fast to See, as well as some fiction writing that he’s been “sitting on” and collaborative works (old and new) with his friend, the writer Julia Gracie-Holland. As a group, these writings are a hall of mirrors reflecting a most fractured time. They reveal an approach to artmaking that is both classic and not-yet-there, a profound intellectual voice, and an unhinged internet-influenced style for a generation that moves fast. Intears creates mazes in his essays and his presentation, an energetic online display that sheds light on a writer’s struggles with sensitivity and certainty, and, like all inspired art, invites multiple, disjointed readings of the situations we encounter.

In this FaceTime conversation, he clarifies his views on contemporary art, energy, and community-building, while analyzing the limits of digital writing, the importance of memento mori, and the complex web of identity, connections, and mystery.

DAVE KESSLER: You started becoming a “serious” writer in 2019. Why are you debuting now?

TIGER INTEARS: I had prepared for years and it suddenly clicked that I could spend my entire life preparing. I was familiar with one pattern: write a piece, email it out to friends. Every now and then I’d get close to thinking of a public presence for my writing, and in 2020 I came close to publishing, but early experiences with some presses plus a few hospitalizations left a bad aftertaste. I needed to make sure I’d be at peace with my words three-, six-, nine months after releasing, and the sort of vulnerable expression I was relying on made me feel ashamed about the work two weeks after putting it out.

I’m no better about that process with Stained Glass Sincerity, but I felt a level of urgency and confidence upon completing it that I hadn’t felt since I was a teenager. I was considering printing the essay as a small book and sending it out to the people in my life who have cared about my writing in the past. Anyway, I quickly decided against that, and wanted a more immediate format, and so I thought of the website. I was quite surprised by how intuitive Quartz felt to use, and I’m very thankful for its creator, and really hope this format picks up. I knew I wanted to use a website that mirrors my writing on the software Obsidian, and not just build a site that would be a collection of works or whatever—I’m interested in the process plus the final outcome but not in uninspired presentations. I have always been excited about the possibility of creating a home online, and after I finished SGS [Stained Glass Sincerity], and felt compelled to share, I said, “Okay, I want to do it on my own terms.” I don’t want to email PDFs anymore—I really feel beyond that.

KESSLER: Let’s stay with the topic of digital presentation. You have an extremely connective style: you bring fragments together within the same piece, and you often use these bright green hyperlinks to connect to other pages on your site. You’ve got a wide array of reference points, and there’s something very internet-y about it all.

INTEARS: There are so many ways to expand on this. Let me just say that I truly believe my interest in creating connections comes from a place of lack, meaning that I often struggle with connections in the profound sense of the word, the “human-to-human” which is one of the dearest things. Most writing that’s out online today isn’t concerned with that, it’s just destructive: a playground for irony, lazy humor, and putting one another down. I am an Arab, and although there’s a lot of corners in the world that would’ve preferred it to be otherwise, I am in love with my Arabness, and it’s been that way since the beginning, and it won’t change. I mention this here because being online as an Arab kid, well it felt like the entire world was against me. It was just so much hate, and that stuff hasn’t gotten any better. You have to be very careful moving online, and I really want to emphasize this phrase online movement, because that’s what you do every day. You jump from page to page and take in everything you encounter whether you like any of it or not.

With my site, I wanted to create something quiet and focused. Because I’m not a web developer, or web designer or graphic designer or anything of that sort, I’m making all sorts of mistakes, and I’m having fun making them. I just want to have a good time with all of this. I think I’m probably just built a little different. I don’t know that many people would want to listen to something like “another night” by Oklou—it’s the song I was listening to before you called—and try to figure out why that reminds them of Prince’s music. Or maybe a lot of people do, I just don’t know that many are bothering with building websites based on the premise of connection-forming. And if there are many who are in fact doing this, and I’m just adding a bit to that space, than that’s great too.

The whole emphasis on focus is also coming from a place of being off social media for about as long as I’ve been a writer for—I mean, it’ll be almost a decade soon. It’s really a very formative step to move away from an online social presence while still caring very deeply about online movement. My concern has always been, How can I be involved without turning my brain to mush in the process? Well thankfully I grew up online and I understand this stuff in very intuitive ways that allow me to take a step back. This is not a flex—Julia [Gracie-Holland] is still on social media and she is much more intelligent and in-tune than I’ll ever be after all. I just know that it’s not good for me or my sanity to be on that stuff, but I also don’t want to be isolated, or be misrepresented as antisocial, so I do my best to stay connected in ways that matter. This quiet view of the internet, to me, seems like a very honest perspective. That’s why I’d hope for visitors to think of the website as a thing in and of itself and not just a vehicle for the writing. The real Tiger expression is in the whole.

KESSLER: In the site.

INTEARS: Yes, in the site, and I geniunely feel that those who have an intimate understanding of online spaces and dynamics, they’ll get something out of it. It’s boring to complain about social media but—

KESSLER: Oh I’d love to hear your thoughts—

INTEARS: We’re just not as good at loving one another anymore, because our attention is so split. This isn’t as kooky as it sounds. This is like, as basic and elemental as it gets. I try not to get nostalgic but I still dream of 2012, and of 2013, and maybe 2014, when the meeting point of social media and regular day-to-day shit was much more vibrant. Now it’s full-fledged narcissism, and unless you have a strong sense of what it used to be like before all this stuff, or else you have a vision of what alternative spaces can look like, it just feels pretty doomed and at the very least boring.

I’m lucky in that the people I surround myself with mostly have interesting takes on social and digital dynamics. They aren’t just zombies, and I really appreciate having that in my life. I value it so much. But there are so many people where I’m like, What are you doing? It’s no wonder that the coast feels so clear, people are tripping on their own shoelaces left and right. Look, I don’t think what I did is the only answer, it’s just one way of doing things and the world knows billions of different approaches—but we’ve got to be a bit more critical, and to really wonder, Is this the way to move forward? People always come up to me and ask how I did it. Like, Tiger how did you do it? And I’d just say it’s the only way that was possible for me. Sticking around would have ended me, really.

KESSLER: Do you ever picture your work being promoted on social media?

INTEARS: I don’t know where I’ll be a year from now, maybe there’s a version of Tiger that promotes in a year. But for me that’s an ethical question: it is a question of encounter, of relationality, and of etiquette. I just want to present things gracefully. I have a standard that I’ve set for myself, and I know how to meet that standard at the moment, but I don’t know if the goalposts will change in a year or ten. They’ve already shifted for me in the past few months and that’s why I’m publishing.

KESSLER: You once described Stained Glass Sincerity as “a breakup work.” Why did it take that form?

INTEARS: I think it’s a bit one-dimensional to think you have to process romantic loss and all that stuff in a very on-the-nose way. I don’t contain my work. To allow and welcome everything that comes up, and to try to put that into words, and then to combine things in a meaningful way, that’s a source of great joy for me, and I don’t take it for granted, not at all, because not everyone has this outlet. It’s therapeutic for me. I consider my writing, and all the art I engage with, as a huge source of relief, because it is guided by sound and movement more than language, even if ultimately the words are the building blocks. What I do has everything to do with contemporary music, and quite honestly very little to do with contemporary art or literature. I just want to take away my pain, and it’s a lovely bonus if I can do a bit of that for someone else. The weird part is that I still can’t fully shake the influence of academia on me—but I try to undercut it. I love works that do that. I don’t mean works that are overthinking it, but just works that take into account everything. When I come across something that is thinking of only one tradition and nothing outside of it, that always shocks me, because I don’t get it. If it came out 100 years ago that’s fine, but in the age of the internet I don’t understand.

KESSLER: You’ve also said in a past interview that you don’t want to leave room for imagination in your writing. Have you always used this approach in your writing?

INTEARS: I find that from the very beginning of my writing journey I’ve been interested in creating a space for an encounter, more so than a fantasy, even though I hope these encounters I create can be a form of escape that’s as good as the best fantasy work out there. I’ve always been fascinated by the way fantasy writers can captivate their audience over the course of a seven-book series or something shocking like that, especially since I am very sparing with my own writing, but of course I have no interest in creating fantasy. I’d like to work with what’s already there, to move it around and show how exciting and surprising reality can be. So encouraging the imagination is a distraction—for now. My sense is that what I have to be doing right now is to operate like a documentary filmmaker, but one who embraces a lot of creative freedom, playing with how truth is presented to create an honest, elusive, and engaging experience. Distortion is often closer to the truth than a photorealistic attitude but we know that already. Actually now that I think of it I don’t know if I want to think of myself in terms of documentary. I do want to ultimately give pleasure. Maybe documentary filmmakers do that but I basically I want to show that the same way I’m having a good time working on all this, that my reader can have a pleasurable experience as well. It would be great to be able to make knowledge sexy again. Something like that.

KESSLER: There’s a utopian promise in your work. At least in the way I see it with the brightness and all the freedom talk. Do you feel like positivity is particularly essential at this moment?

INTEARS: I don’t know about any of that. I just follow my gut as much as I can. I’m not so sure my mentions of freedom have idealistic connotations. I’m glad you didn’t call my writing dystopian though, because that feels far from what I do, beyond the surface-level reading. It’s just all about building an open map that takes into consideration beauty and suffering and everything in between. To me, that’s what matters. We all know what’s going on in the world, how cracked all that is. I just don’t want nuance to be lost, and that’s where complacency—which really is the devil—that’s where that comes from.

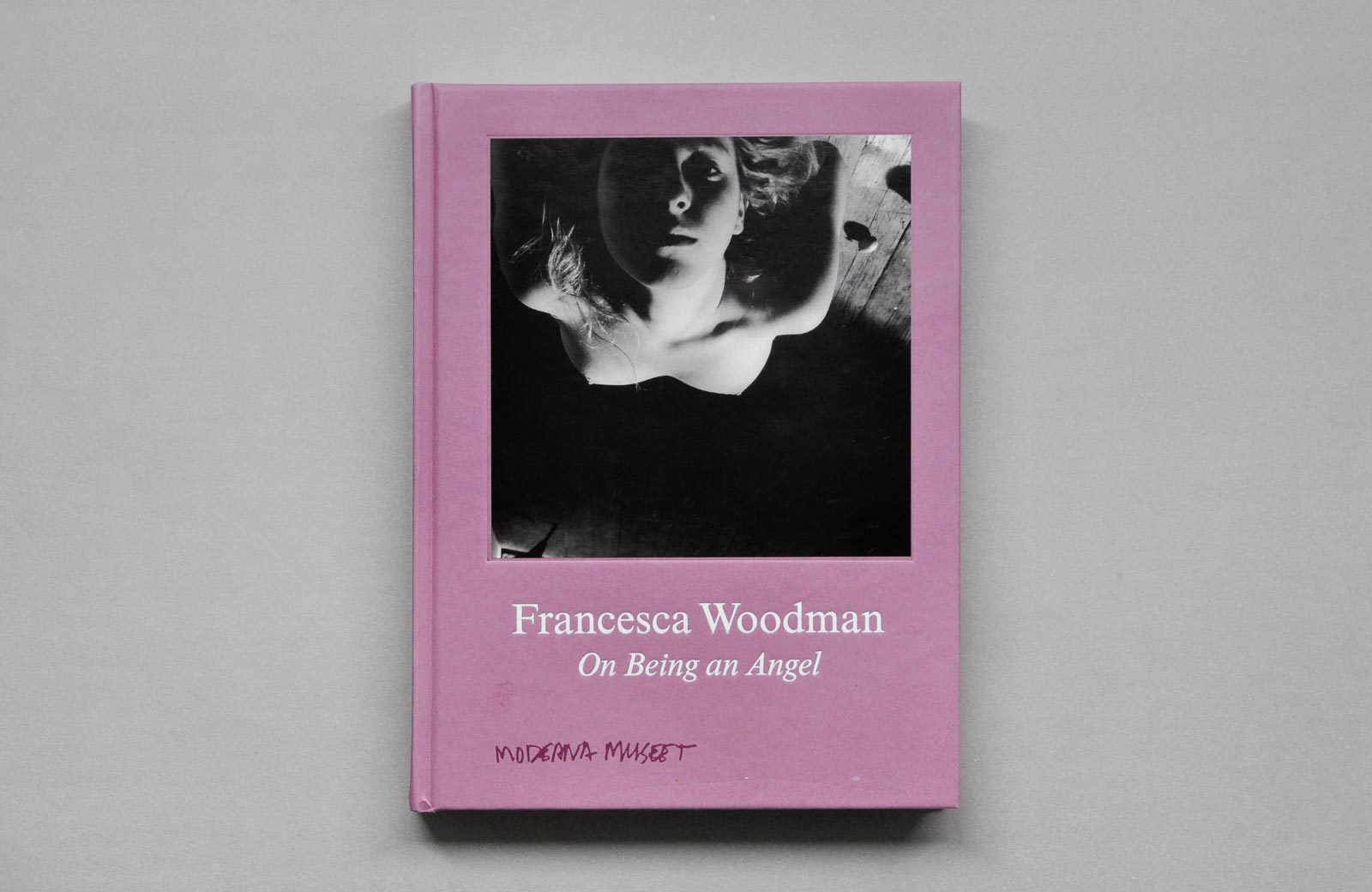

What I care about is dynamism. If there is any overarching theme in the work I am making at the moment, it’s that we’ve got to constantly move if we want to be angels. Now not everyone cares about thinking in these terms. It’s old school or punk or something. I don’t care about labeling it but I think it’s necessary to think in such terms. There’s a book about Francesca Woodman that I no longer have, but in there somewhere there’s a quote about angels and aliens being parallel terms. That excites me. That’s two very energized concepts coming together, like think of the possibilities. Okay, maybe it’s idealistic. That’s just how I’ve always thought, I just feel so much more sure of how I want to articulate and present this now. I think it’s an energy story. And that’s just about the only narrative I’m interested in telling. All other stories put me to sleep, especially stories involving institutional posturing.

KESSLER: Can you elaborate more about the energy story? What’s this narrative?

INTEARS: There are those who want to reduce, through labeling things and then dismissing them, and then there are those of us who want to open up the framework: the excited activators. “Oooh what does this button do?” We’re sort of like Dee Dee in Dexter [Dexter’s Laboratory, the 1996-2003 Cartoon Network show], just naively pushing all these buttons we’re not supposed to. And the result is always a disaster—but it’s fun and that’s where the fruitful spaces are. When we’re children, that’s the sort of curious outlook we have towards the world, and then that orientation is stolen from us. Well if you’re lucky you find that space again. You know Dexter does end up fixing shit, so maybe we do need these Dexter-figures in our lives to prevent total chaos, but I just feel like the art world has too many Dexters and not enough Dee Dees, and we’ve got to address that. Think of playing the game GTA [Grand Theft Auto] as a kid and think of the map at the start of the game when most of it is blurry. If you drive a car into this blurry part of the map, you end up with wanted stars and the cops start chasing you. I think that’s what activators do, they go into the blurry terrain even if it’s got all these repercussions, and it’s the same with art. Some people are too afraid of the BUSTED or WASTED message you get when you mess up in GTA. But in truth you bounce back—yeah you lose some things along the way, but then you pull out a cheat code and it’s all back there. [Laughs] I’m just trying to say activators take more risks. This is why I keep mentioning Terrence Malick. He took one of most interesting risks in contemporary art in the stretch from To the Wonder to Song to Song, real genuine soul-searching is taking place in these two films and also in Knight of Cups, but so few people paid attention. It’s just so sad reading that Malick started having second thoughts about the non-narrative approach after so many critics gave him a hard time. I mean here’s the guy who basically built an entire reputation around trusting your instincts. I’m not saying his return to narrative was a step back, but I also feel like the criticism made him love himself less or something—I don’t know. I’m not really sure what I’m trying to say at this stage, beyond the fact that the energy story is a story of risk-taking and not a complacent rehashing of what’s already there. Anything that keeps risk close and mediocrity at bay is a good thing. I feel very strongly about this.

I hope none of this sounds like it’s coming from a philosophical or intellectual place, and I’d really like to stress the sense of urgency I feel about all of this. A lot of scary things happened around the time of my illness and hospitalizations that could’ve destroyed me. I know we’re not supposed to say this, that it’s wrong to be so honest, but I have an intense awareness of death, and I’ve had that from an early age. If there’s any message I’d like to convey with this energy talk, it’s that it’s entirely natural to keep death in mind often. Of course you can’t be narcissistic about it, or let it get you into a dark place. Really, no, don’t make it your identity. Just have it be enough of a part of your life so that the superfluous, unnecessary stuff is filtered out. If you’re honest in your search, you’ll find that the only way forward is to be an activator too.